2010/10/26

No. 100: Yasuhiro Nakasone, "100th Special Issue - The Future Direction of Japanese Diplomacy"

[PDF version]

Diplomatic principles

As I watch the statecraft of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), whose administration came into being as a result of the first-ever drastic change of government in postwar Japan, what worries me most is the lack of firm diplomatic principles. Japan has shaped its postwar diplomacy by coordinating Japan's inherent diplomatic claims, policies and strategies in light of its relations with other counties, the United States being the most important ally. Thus the foreign policy of the Liberal Democratic Party, which had ruled most of postwar Japan, was based on the so-called Yoshida doctrine designed to restore national sovereignty as well as Prime Minister Ichiro Hatoyama's efforts to establish Japan's independence by restoring relations with the Soviet Union and rearming Japan, which led to current Japanese diplomacy. Announcing an Asia-centric foreign policy on assuming the prime ministership, however, Mr. Hatoyama's grandson, Yukio, failed to pay enough attention to postwar diplomatic tradition and history.

An obvious example was the problem of the relocation of the US Futenma Air Base. I have been arguing as one of my four diplomacy principles not to mix domestic policies with foreign policies (the other three principles will be discussed later), because the latter involves negotiations with other states. The problem with former Prime Minister Hatoyama was that he treated the Futenma issue as a domestic issue without considering the long-term impact or paying due attention to the relationship with the United States. The relocation of US bases is basically a diplomatic issue. How could a state possibly stipulate where to move a certain base without due negotiations with its ally? The mix-up handicapped the DPJ administration by causing the US to view it with suspicion.

Current Prime Minister Naoto Kan needs to eliminate the handicap. To do so, he needs to reaffirm Japan's traditional diplomatic stance as well as his own long-standing diplomatic beliefs at major international summits. What counts on the international stage is personal trust. I have already advised Mr. Kan to make friends with national leaders, with whom he would be able to work during summits. Such friends can only be obtained through steady, behind-the-scene efforts involving personal exchange and correspondence. The prime minister should not spare such efforts.

In diplomacy, a state's stance may at times conflict with those of its counterparts. The state may often find itself in situations in which it cannot basically make any concession. There are also cases in which domestic public opinion clashes with international claims that the state is advancing in the international community. The Japanese prime minister must be prepared to break through such a standoff with outstanding foresight and strategy.

Generally speaking, important foreign policy decisions, those pertaining to Japan-US relations included, must be made in light of three criteria: international law, their long-term impact three to five years out, and national interests. In addition, I believe, Japanese diplomacy needs be based on the following four lessons learned from the experience of the Great East Asian War: 1) never venture out on things beyond one's national strength; 2) never rest diplomacy on a gamble; 3) never mix domestic policies with foreign policies, and 4) take into account world trends. Japanese prime and foreign ministers need to consider their foreign policy options according to these criteria and lessons and after paying enough attention to Japan's diplomatic traditions and history.

East Asia diplomacy

As for specific issues, East Asia will become increasingly important. In the region, Japan lags behind China, which is actively developing its East Asia diplomacy. In particular, China is bolstering economic ties with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as was symbolized by the formation of a free trade area early this year. The country is aggressively yet flexibly strengthening a comprehensive cooperative relationship with ASEAN countries. China is also exercising leadership in the Six-Party Talks. East Asian diplomacy will become a real test of strength for the Japanese prime minister.

In developing a strategy toward East Asia, the prime minister will need to envisage a distant future in which East Asian countries eventually establish a community. He should do so with a careful study of the European experience.

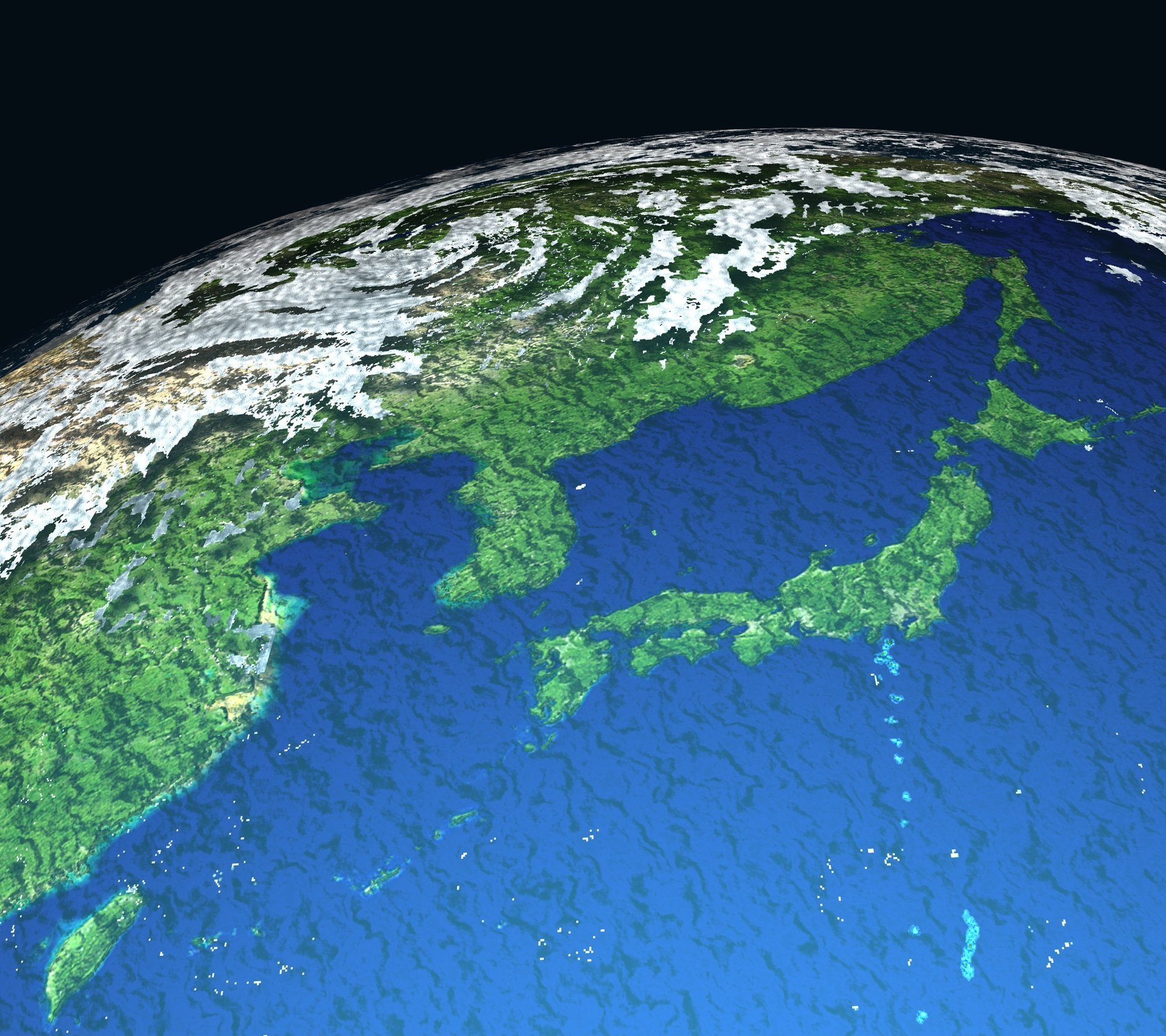

Having proceeded from the European Community to the European Union, European countries today share the same currency and parliament and even appoint a president (President of the European Council). Behind the remarkable progress lies the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which established and has maintained peace in Europe. The security and stability assured by NATO has given a boost to European integration thus far. East Asia lacks such an integrated security framework, but has instead been covered with a web of American security networks. The Asian seabed is enmeshed in American bilateral alliances, including those with Japan, South Korea, Thailand, and Singapore. There is also a security treaty for the defense of the Pacific Ocean, which was formed among the US, Australia and New Zealand. There is no denying that the increasingly dense economic networks in East Asia rest on the sense of peace and stability provided by the security web. Without realizing that the Japan-US alliance constitutes part of the crucial security network, any effort to promote an Asia-centric community will be bound to fail.

Japan's relationship with China, which had been improving until recently, is facing new challenges. As next-door neighbors, Japan and China have a very complex history. Japan is tied to a past of having caused great harm in the previous war to China, which has now emerged as a great power in terms of population and national wealth. When I sought advice from Soho Tokutomi (1886-1957), a journalist and politician, he said on Sino-Japanese relations, "Get on with China. As a matter of fact, you have to be aware that it was Japan that created the trouble." Difficult as it is, the two countries share the need to overcome hardships and build a friendly relationship. China has overtaken Japan in gross domestic product, but Japan should remember that it has its own distinct culture and technology.

In order to maintain good relations with China, Japan needs a skillful strategy of shaking its right hand with the United States and its left hand with China. We must not forget that the recent incident over the Senkaku Islands occurred at a time when the new DPJ administration had yet to build firm relations with the US.

The United States will surely have no intention to exchange fire with China but, when it comes to China's ideological attitude or actions that go against international common sense, the US takes a firm stance, determined to right wrongs from the viewpoint of a world state in charge of maintaining international order. At a meeting of the ASEAN Regional Forum held in July, for example, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton warned against China's claim to sovereignty over the South China Sea. Japan should make clear that it shares the basic American stance and will act in union with the US.

Political leadership

"Political leadership" is a buzzword of the DPJ administration. What the term really means is that a prime minister leads in state affairs based on his/her philosophy, strategic visions and ideas. He/she may be open to the advice offered by people around him/her, but it must be the prime minister who exercises initiative and directs Cabinet ministers in achieving policy goals. In other words, political leadership is close to presidential politics conducted in a presidential manner. Most important in presidential politics are philosophies, ideas, strategies and comprehensiveness--crucial qualifications for statesmen. I regret to say, however, that they are hard to find in today's political circles.

What philosophies and ideas should guide Japan in the long term? What strategies and comprehensive visions should lead the way? These are questions we Japanese need to ponder.

Yasuhiro Nakasone is former Prime Minister of Japan. He is now Chairman of the Institute for International Policy Studies.

The views expressed in this piece are the author's own and should not be attributed to The Association of Japanese Institutes of Strategic Studies.