2014/09/08

Futoshi Matsumoto, "Outlook for the Middle East in 2014: The Middle East, Three Years On from the Arab Spring"

[PDF version] (The article appeared originally in Japanese in IIPS Quarterly, dated July 18, 2014).

The world is in a state of flux.

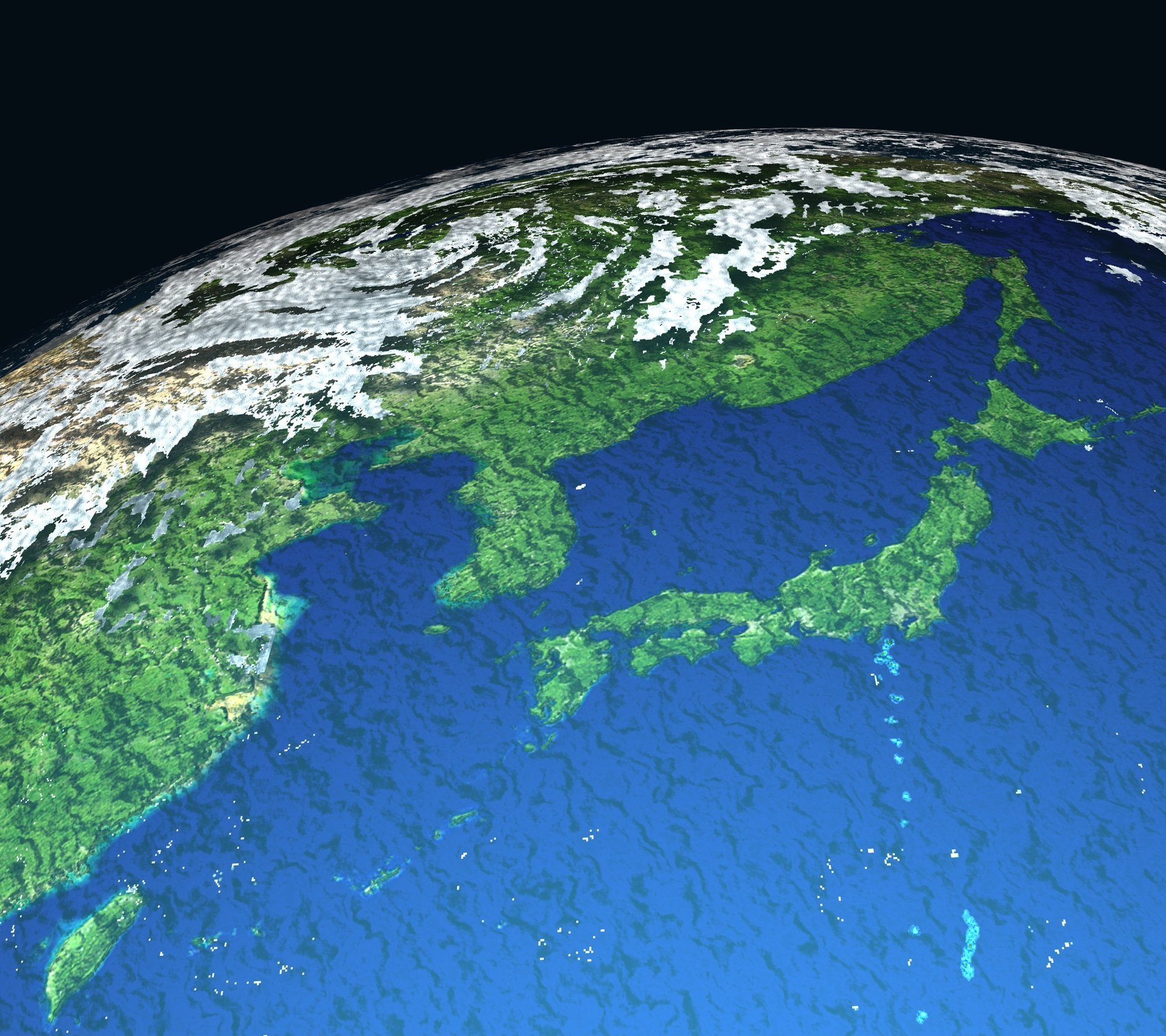

In East Asia, the rise of China and its aggressive maritime expansionism--the result of newfound strength and its attendant changes to the status quo--are making waves in the East China Sea and the South China Sea. In Europe, Russia is brazenly flexing its muscles and beginning a tug-of-war with the EU and the US over Ukraine.

In the Middle East, even national borders that had been quite clear until about three years ago have grown progressively more indistinct. After the collapses of anciens régimes, power vacuums are now ubiquitous. Jihadism and sectarian conflicts are raging out of control, and a new order is yet to emerge.

For instance, a semi-independent region controlled by Kurdish forces has appeared along Syria's border, and an Islamic extremist organization, the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), has even managed to take control of cities, mainly in Syria and the northern part of Iraq, and make them autonomous from central governments. This poses fundamental doubts as to whether the chaos in the Middle East will settle down in the near future.

In this paper, I would like to explain what this tumult in the Middle East represents, three years on from the Arab Spring, as well as to consider the future prospects going forward.

A great quake from multiple tectonic shifts

In The Breaking of Nations, a book published the very same year that the Iraq War began, Robert Cooper--then a senior EU official--categorized the countries of the world as belonging to one of three groups: premodern, modern, or postmodern. These classifications are useful when considering the Middle East after the Arab Spring.

That is, to solve the puzzle of the present chaos in the region, one may imagine the simultaneous tectonic shifting of three giant "plates": one plate consisting of postmodern movements symbolized by youth who use Facebook, another of movements seeking the establishment of as-yet unfinished nation-states, and a third of bloody premodern movements, as exemplified by intense sectarian conflicts. As these three separate plates churn under the surface, the ground of the region is constantly shaking in every direction, as if in a great, unceasing earthquake.

To grasp the current upheavals in the Middle East properly, one must look back through modern history to a time when, following World War I, the framework for today's Middle Eastern states arose through the artificial setting of borders by the UK and France.

As a result of their origin, nations in the Middle East have always been buffeted by transnational movements that pay no heed to these contrived "nation-states" and that seek identities beyond those conferred by national territories. Two examples of this sort of movement are the previous Pan-Arabism as well as the current-day Islamist movements. The unending series of Middle East crises also inevitably depends to a great extent on ancient, subnational ties, particularly sectarian and tribal ties.

In other words, the Arab Spring has violently shaken up both nation-states and the premodern understanding that the peoples of the Middle Eastern region have about their own identities.

The vanguard of the Arab Spring: Egypt and Tunisia

The Arab countries today could probably all be placed roughly into one of three groups:

The first group consists of Egypt, a regional power, and Tunisia, where the Arab Spring began. Both Egypt and Tunisia have relatively simple ethnic and religious compositions, and they are also highly mature nation-states. These circumstances have given the countries an edge in riding out the high waves of the Arab Spring.

In Egypt, a new constitution was adopted in January with the support of over 98% of the population, and--under the guidance of its military--politics is in the process of normalization. After two dramatic regime changes in just these past three years, the Egyptian people have finally come to abandon the chaos of revolution and to desire stability fervently.

Leading up to this, the Muslim Brotherhood, which won the first general and presidential elections following the revolution, monopolized national politics, turning a blind eye to the wishes of the military, the secularists, and the youth who had supported the revolution. The Brotherhood dogmatically pushed through a strongly Islamic constitutional amendment and other legislation. They also allowed encroachments into the country by Islamic extremists, ushered in a deterioration of the domestic peace, and were unable to draw up plans for economic recovery; these failings disappointed the Egyptian people, to say the least.

In the presidential election held at the end of May this year, former defense minister Sisi rode a strong wave of popularity among the Egyptian people to his election. From this point on, Sisi will presumably continue his thorough suppression of the Brotherhood, which has remained a significant and baleful influence on Egyptian politics after the revolution. Thus, under the military's leadership, there should be attempts at recovery in both public order and the economy. Egypt, after all, has no other choice.

In January 2014, Tunisia's Constituent Assembly produced a comparatively moderate new constitution through compromise between Islamists and secularists. Among the Arab nations that have experienced the turmoil of the Arab Spring, it is thus Tunisia that is on the verge of finding a path to normalization.

Unrest in the Gulf monarchies

The second group is the Gulf monarchies. The kingdoms of Jordan and Morocco could also be included, though they are not geographically part of the Persian Gulf region.

These states, at first glance, appear to have just managed to ride out--for now--the political turmoil that has followed the Arab Spring. The Gulf monarchies have barely managed to contain the protests brought on by the Arab Spring.

Many of the Gulf states have spent lavish, almost ridiculous, sums on policies to pacify their peoples during this time. This provides a clear demonstration of how the distribution of petroleum income has had a strong effect on maintaining regimes--beyond even that conferred by historical legitimacy.

Such developments in the Gulf states are superficially the result of revolution. And yet they can also be considered victories for anti-revolutionary forces in these monarchies. However, on closer inspection of conditions in the Gulf states, the Arab Spring continues to have a profound effect on these countries' security environments.

The most significant phenomenon is further entrenchment of sectarian strife. This single outcome is the complicated result of various factors coming together, including domestic political contradictions within the Gulf states, confrontations over power within the region, and an indecisive US policy toward the region. In the near future, it is possible that cracks that have developed in Gulf state societies as a result of the Arab Spring will, in due course, grow.

States in decline: Libya, Yemen, Syria, and Iraq

Changing focus to the third group in this region, one finds a group of nations that well represent the premodern aspects of the region: Libya, Yemen, and Syria.

The future of Libya--a country to which the international community lent its support in toppling the Gaddafi regime--is particularly difficult to predict, as the central government in the capital of Tripoli has extremely little capacity for governing the entire country. Currently, as many as 1,700 warlords (according to one estimate) are operating unchecked outside the capital. In particular, the extremist organization Ansar al-Sharia and al-Qaeda-affiliated organizations are also gaining ground at the same time that Federalists are gaining power in Libya's east.

For Libya, which has never in its history experienced democracy, this result was inevitable after the authoritarian and dictatorial regime of Colonel Gaddafi was toppled. Worsening even further the overall Middle East situation, weapons have found their way out of the regime's armories and are spreading far and wide, thus continuing to spur chaos in the region.

The situation in Yemen resembles that in Libya. In particular, the al-Qaeda-linked organization that calls itself al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) is taking advantage of a weakened central government to ride roughshod over the country, leading to appalling circumstances, particularly in the capital of Sana'a and in the country's south.

In Syria, more than 150,000 people have been killed, and the chaos is worsening. Even if the relatively simple rupture between regime and anti-regime forces were to be healed, it would still be too late to resolve the country's more fundamental problems. With an influx of jihadists, Syria's progress toward becoming a modern nation has halted, and sectarian conflict is becoming all the more stark. In other words, this represents the essential, unresolvable tension between the modern and the premodern.

There are now signs that the infighting among the Islamic State and other Islamic-tinged anti-regime forces, which began at the start of the year in Syria's north, is beginning to end. This is because nationalist sentiments among the Syrian people can no longer tolerate ultra-radical Islamist rule.

Bashar al-Assad won re-election as president in the June elections. The regime considers resistance against Islamic extremists its raison d'être and should continue to intensify its offensive against the anti-regime forces.

Finally, it is necessary to touch upon one more country: Iraq. In more ways than one, Iraq itself suggests what might be the eventual result of the chaos in the region.

In a process unlike the spontaneous uprisings that have removed tyrants in recent years, Saddam Hussein's dictatorial regime was toppled via external deliberations that led to the Iraq War. After this, there was repeated trial and error in what would appear to be anticipation of the Arab Spring. Even 11 years after the start of the Iraq War, there is still a tense tug-of-war between those on the side of premodern sectarian strife and those on the side of rebuilding the nation.

After the Iraq War, the forces associated with the old regime transformed themselves into Islamic extremist groups and have continued to fight the government using terrorism. In Iraq, the central government--on which the Iraqi people ought to be able to rely--remains weak, fostering ever-stronger reliance on tribalism and encouraging radical sectarianism.

Thus, to this point, the Maliki government behaved in an authoritarian manner and was unable to find a way to govern the country effectively. In such a situation, the Iraqi people receive more benefit from pledging their allegiances to their respective tribes and religions than from pledging it to a weak state, and so there may be nothing that can be done. The Maliki government's authoritarianism has distanced Sunnis from the centers of political power, leading to the fiasco of ISIS reoccupying major cities that are Sunni strongholds, including Fallujah and Mosul. And it was only natural that Prime Minister Maliki was finally thrown out of his post this August due to heavy pressure from within and without.

Security in the Gulf region and the Iranian nuclear issue

There is actually something else that will affect the futures of the Arab countries now being buffeted by the Arab Spring: developments in their neighbor Iran.

This is true in two senses. First, the ultimate fate of nuclear negotiations with Iran is likely to affect the security of the Gulf states as a whole. Second, Iran's policies may also impact the future of the sectarian conflict spreading throughout the entire region.

In the background is a situation in which Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf states have no choice but to focus on the structures of sectarian conflict between Sunnis and Shias in their policymaking in an attempt to resist Iran's expanding regional hegemony.

Iran's Rouhani administration, which was inaugurated last August, has demonstrated its willingness to engage in earnest negotiations over the nuclear issue. The initial agreement that Iran made with the EU 3+3 grouping last November is already giving rise to a de facto détente between Iran and the rest of the international community.

These dynamic developments are ongoing, and the chance that they will make great changes to the structures of sectarian conflict in the region deserves serious attention.

Rebuilding the nation-state with the people

Having examined the situation in the Middle East, there is an obvious truth that there is but one way out of this chaos: Full-fledged nation-states, in which ordinary citizens are the principal actors, must be reconstituted, and some way of building a stable security environment that encompasses the regional power of Iran must be found.

In somewhat simplified terms, current international problems concerning China and Ukraine all relate to frictions among powers--including China itself, as well as Russia--and can be thought of as converging with issues of resurgent nationalism. In the Middle East, however, more premodern factors of sectarianism and Islamism are relevant. Furthermore, the power vacuums that have continued to expand since the Arab Spring are encouraging such phenomena.

It is uncertain whether these unfinished nation-states, buffeted by changes to the global order and the resurgence of regional powers, will be able to extract themselves from the quagmires resulting from ever more entrenched radical Islamism and sectarian conflict.

And yet, it would be nearly impossible to reverse all of a sudden the long course of the regional dynamism since 100 years ago. Much time has passed since modern states first arose in the Middle East. Their resiliency is far stronger than we can even imagine.