2015/02/02

Futoshi Matsumoto, "What Lies Ahead in the Stormy South China Sea?"

[PDF version] (The article appeared originally in Japanese in IIPS Quarterly, dated November 14, 2014).

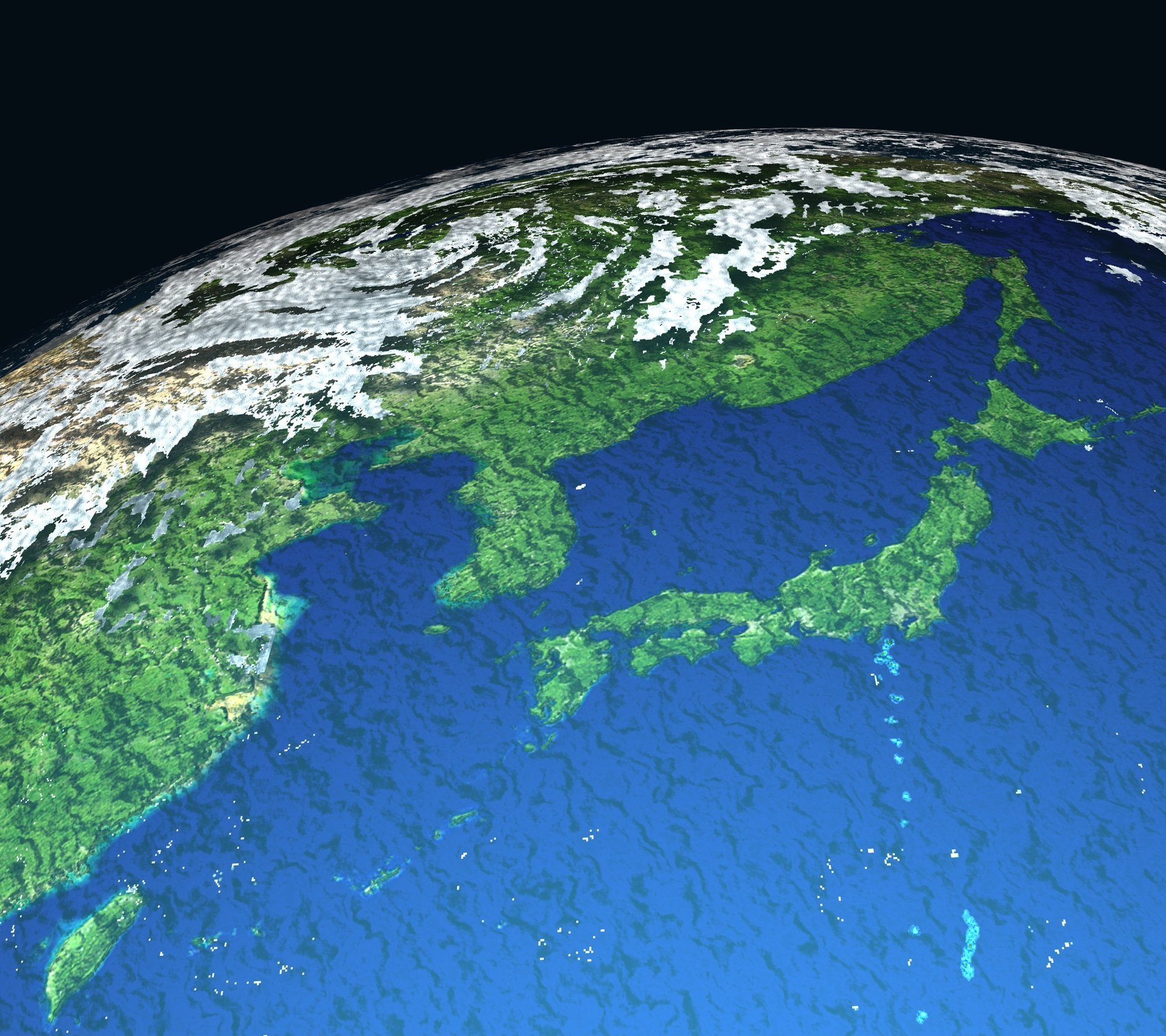

The international order in East Asia is on the brink of crisis. What were until recently no more than a few ripples have now become a powerful tsunami that could engulf the entire region. This is due to China's ongoing and blatantly illegal use of force in the East China Sea and South China Sea.

On July 1, 2014, in speaking of his nation's confrontations with China in the South China Sea, Vietnam's supreme leader Nguyen Phu Trong, the secretary-general of the Communist Party, asserted that "some are asking whether we are at war. If this is the case, we must prepare for all eventualities."

When, in early May 2014, the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) set up a large mobile drilling platform, the Haiyang Shiyou 981, off the Paracel Islands and began drilling for oil, the relationship between China and Vietnam effectively moved one step closer to war. As a Communist Party ideologue, Secretary-General Trong has been the highest ranking figure involved in maintaining amicable relations with China. The fact that the secretary-general uttered the word "war" in reference to relations with China speaks volumes about the gravity of the situation.

Meanwhile, in June, President Aquino of the Philippines compared Chinese actions to the aggressions of Nazi Germany, in reference to China's repeated and seemingly rapacious moves with regard to a number of islands in the South China Sea that are governed by the Philippines.

China's blockade of the Scarborough Shoal between April and June 2012, the subsequent dispatch of Chinese patrol boats to the Second Thomas Shoal (or Ayungin Reef) to carry out obstructive operations, as well as a series of acts of force seemingly geared towards the future construction of airstrips (including the transportation of soil and sand to reefs in the South China Sea that are effectively under Chinese control) have served to enrage President Aquino and the Philippine people.

A China that steadfastly maintains its core interests

In all these cases, a major cause of the anger towards China has been the fact that its actions have not had the consent of the other party in the dispute--Vietnam or the Philippines--and have been principally informed by the use of force (with no regard for international law) in the shape of a general mobilization of Chinese fishing vessels, Chinese coast guard patrol boats, and warships of the People's Liberation Army Navy.

Domestically, China has been actively defending these moves on the grounds that it is compelled to maintain its core interests. That is to say, it would be willing to resort to actual military force to protect Chinese national (or core) interests. Consequently, this logic would appear to contradict the notion of China's "peaceful rise"--the course that it has hitherto espoused.

The principle once advocated by Deng Xiao-ping, "hide one's talents, bide one's time, and seek concrete achievements," was expressed in updated form in 2009 by then-General Secretary Hu Jintao as "hide one's talents, bide one's time, and actively seek concrete achievements," and China's current approach is in line with this newer articulation.

More specifically, China's active pursuit since 2008 of all-out maritime expansion that is not in conformity with international law--in both the East China Sea and South China Sea--has resulted in the current crisis.

There would appear to be three underlying reasons for this:

First, it represents an expression of confidence by China as a state that is supportive of nationalism within Chinese society. In particular, as Western nations verged on economic ruin in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, China came to exhibit an excess of self-confidence deriving from the fact that it weathered the economic storm by means of large-scale public spending and from its successes in terms of yet further economic progress. This seems to have manifested itself in the form of arrogant behavior towards other countries.

Second, contrary to this superficial veneer of self-confidence, there was an undeniable intensification of political and social unrest in the form of so-called "mass incidents" (such as crowd riots). The term "mass incident" is used in China to refer to a disturbance or breach of the peace caused by a crowd of people, such as a demonstration or a riot. According to one estimate, such incidents total as many as 180,000 per year. One solution for dealing with this kind of domestic conflict exhibits itself as a tendency to encourage nationalism and to incite active expansion overseas.

Third, the medium- to long-term maritime strategy of China's People's Liberation Army (PLA) must not be overlooked. For the Chinese navy, which has been undergoing steady modernization with a view to establishing itself as a blue-water navy, securing the freedom to operate in the East China Sea and South China Sea is a fundamental prerequisite to establishing regular operations in the western Pacific Ocean beyond the first island chain and out as far as the second island chain.

In short, China's overseas expansion is informed by the complex interplay between three principal elements: China's self-confidence, its domestic unrest, and its military strategy.

China's "Salami slicing tactics"

What, then, are the characteristics of China's overseas expansion in the South China Sea, often termed as "Salami slicing tactics"? Two prominent features are particularly noteworthy of note, as follows:

One characteristic is diplomatic bluster and the exercise of force that does not necessarily rise to the level of the use of armed force.

The instances of the use of force against Philippine and Vietnamese fishing vessels by Chinese coast guard patrol boats are a case in point. So far, quite a number of Philippine fishing boats have been obstructed by Chinese patrol boats as they neared the Scarborough Shoal or the Second Thomas Shoal. Off the coast of Vietnam, many Vietnamese fishing boats have been rammed by Chinese patrol boats, causing injuries to fishermen as well as damage to the fishing vessels.

For over two months, the Haiyang Shiyou 981, a large drilling platform, was positioned off Vietnam and served, as CNOOC stated, as "mobile national territory" and as a "strategic weapon."

A second characteristic of this Chinese expansion is that it involves systematic cooperation between a variety of different actors.

For example, according to a statement issued by the Vietnamese government on June 5, 2014, it is clear that China has adopted a so-called "cabbage strategy."

In order to protect the large drilling platform, China for a time deployed as many as 140 vessels (warships, policing vessels, and even fishing boats) in a controlled, multilayer formation resembling the leaves of a cabbage--with the various different organizations involved operating under tight official supervision.

The undercurrent to this is that China has evidently adopted deliberate tactics of using the State Oceanic Administration (SOA), a non-military organization, and the nation's fishermen as a "maritime militia," rather than putting the People's Liberation Army at the forefront of operations. More to the point, these non-military organizations are deployed in close cooperation with, and specifically under the control of, the PLA.

The strategies of the Philippines and Vietnam

In confronting China's use of force, the Philippines and Vietnam are now beginning to adopt a strategy that clearly differs from their previous strategies.

Broadly speaking, this involves taking concrete steps to increase their deterrence capabilities, strengthen cooperation, and engage in the so-called "three warfares."

First, they are increasing their deterrence capabilities.

Vietnam has already purchased six Kilo-class submarines from Russia, and these are due to be fully deployed by 2016. Vietnam is also to receive assistance from the Indian navy in the form of training in submarine operation. As a result of the confrontation that began in early May 2014 over China's drilling platform, it was agreed during Foreign Minister Kishida's visit to Vietnam in the summer of 2014 that Japan would sell Vietnam six used maritime surveillance vessels.

For its part, too, the Philippines is expected to further increase its maritime security capability in the future, with the Philippine coast guard due to acquire patrol boats from Japan, France, and the US. When President Obama visited Manila in April 2014, the two nations concluded a new US-Philippine military cooperation agreement, and it was agreed that US naval fleets would make periodical stop-offs in the Philippines. The US also plans to provide the Philippines with training facilities and coastal radar installations.

Second, the two nations have made conspicuous moves towards cooperation with other countries--principally under the rubric of the ASEAN claimant states (states that are making claims of sovereignty).

Particularly striking is the strengthened cooperation between the Philippines and Vietnam themselves. In addition to this, there have been increasing contacts and exchanges of views between these two nations and the other ASEAN claimant states, such as Malaysia and Brunei. There have also been conspicuous advances in cooperation with third-party nations that have coinciding security interests, such as Japan and the USA.

Third, both the Philippines and Vietnam are actively engaging in the so-called "three warfares" at which China is so adept--psychological warfare, media warfare, and legal warfare.

In January 2013, the Philippines initiated arbitration proceedings against China based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. At the end of March 2014, it submitted to the International Court of Arbitration a voluminous statement that included its opinions on the legal status of so-called "islands" in the South China Sea. This legal warfare waged by the Philippines could, in large part, also be seen as a major escalation in its media warfare against China.

The Philippine government has widely distributed photographs to the international community that were taken by the Philippine navy and air force, which show China engaging in activities such as the transportation of sand and soil to islands that are effectively under China's control. It has thereby tried to thwart China's attempts to create faits accomplis.

For its part, Vietnam staged almost daily press conferences at the time of the affair involving the CNOOC drilling platform, detailing China's use of force at sea--even going so far as to publish video of Chinese patrol boats ramming Vietnamese fishing boats. Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung has also suggested that, if China persists with its stubborn attitude, Vietnam might--like the Philippines--institute legal proceedings.

What lies beyond the maelstrom in the South China Sea?

In mid-July 2014, China suddenly withdrew the large drilling platform from the vicinity of the Paracel Islands one month ahead of schedule, so the tensions with Vietnam are in abatement for now. China likely did this with a view to ensuring the success of the APEC conference that was scheduled to be held in China in November 2014.

China is at last agreeing to begin talks on a code of conduct (COC) for the South China Sea, as is fervently desired by the ASEAN nations, and China is calling on the ASEAN nations for cooperation on maritime issues over the coming year.

Whether or not these superficial changes really signify modifications in China's foreign policy and security policy must remain open to serious question.

As US Secretary of State John Kerry succinctly put it in his remarks at the East Asia Summit Ministerial Intervention on August 10, 2014, "lack of clarity...with respect to [territorial] claims [such as China's 'nine-dash line']...has created uncertainty." China, however, has completely failed to respond to the arbitration proceedings based on the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea that were initiated by the Philippines. The fact is, China understands how weak the legal basis of its case is and thus rejects such overtures out of hand.

Instead, China is currently bringing in sand and soil to reefs that are under its effective control, and it is planning to build airstrips on them at some stage. China's thinking in this instance is probably that it would like to acquire long-range maritime surveillance capability that matches that of the other claimant states.

There is no denying the fact that some of the ASEAN nations are, as ever, strongly inclined to maintain amicable relations with China, particularly the smaller states that are beneficiaries of economic largesse from China. At the same time, it is utterly inconceivable that China can regain the trust of Southeast Asian countries such as the Philippines and Vietnam that it has lost so completely over the past few years.

In any event, the nations that border the South China Sea appear to be further upgrading their maritime surveillance capabilities and making increased efforts to build deterrence capabilities in the face of China's maritime expansion. Specifically, Southeast Asian countries will need to strengthen their deterrence capabilities in security terms--this will involve developing their defense capabilities and moving more quickly than in the past to build coalitions and enter into effective alliances with friendly nations such as Japan and the USA.

It is in this context that the Japanese government's April 2014 revision of Japan's Three Principles on the Control of Arms Exports has fueled increased expectations among Southeast Asian nations of future security cooperation with Japan.

Whether the outcome will be that a security dilemma will arise involving China and Southeast Asian nations, or that they will prove able to construct a collaborative security environment in the region, will largely depend on the manner in which China's mounting internal contradictions will play out.

If actions that are damaging to the international order continue, it must surely be expected that the international community will react even more strongly and that the East Asian order may risk being lost in a maelstrom.