2015/06/23

No. 213: Hirofumi Tosaki, "Nuclear Arms Control after the NPT Review Conference: The Need for a Realistic Approach in the Face of Geopolitical Competition"

The quinquennial Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference (RevCon) in April-May 2015 concluded without adopting a consensus final document due to disagreement over convening a conference on a Middle East Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD)-Free Zone. Nevertheless, the subject that prompted the most heated debates among participating countries over the four-week session was nuclear disarmament, as was the case in past RevCons.

Among the issues discussed, the most contentious as well as spotlighted issues were whether and how to engage in normative/legal approaches for nuclear disarmament, such as by addressing "the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons" and establishing "a framework for the prohibition and elimination of nuclear weapons." At the Conference, 107 non-nuclear-weapon states (NNWSs) -- mainly members of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the New Agenda Coalition (NAC) that have grown increasingly frustrated over the insubstantial progress made on nuclear disarmament, particularly after the entry into force of the US-Russian New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) in February 2011, and, more fundamentally, over the discriminatory nature of the NPT regime -- joined the "Humanitarian Pledge" proposed by Austria, in which they "call on...to identify and pursue effective measures to fill the legal gap for the prohibition and elimination of nuclear weapons." Furthermore, some of them even called for commencing negotiations on a nuclear weapons convention with or without the participation of the nuclear-weapon states (NWSs).

It is obvious that normative/legal approaches are essential for reframing the nuclear disarmament debate and achieving a "world without nuclear weapons," especially from a medium- to long-term perspective. However, it is also clear that such approaches could hardly play an effective role in tackling the root cause of the current deadlock in nuclear disarmament: deteriorating relationships among the major powers involved in deepening geopolitical competition in key (sub-) regions, particularly Asia and Europe, during the ongoing power transition.

In those (sub-) regions, both revisionist and status quo countries have attempted to maintain and/or strengthen their nuclear (extended) deterrence, and to reaffirm the value of nuclear weapons as "structural power." For revisionist states seeking to reconfigure the existing international/regional order or expand their spheres of influence, nuclear weapons serve as one of the most significant assets for demonstrating their power explicitly or implicitly. For status quo states facing the challenges posed by such revisionist states, there are few alternatives but to react to such a movement and seek to maintain the reliability of nuclear deterrence while engaging in the power struggle over the international/regional order.

In the security circumstances mentioned above, one would hardly expect the NWSs to be willing to accept radical nuclear disarmament in accordance with normative/legal approaches. NWSs -- and, to a lesser extent, the so-called "nuclear umbrella states" -- are cautious about the possibility of decreasing their power by accepting nuclear disarmament, which has been oft-regarded as a part of the power struggle. Therefore, NWSs repeatedly demanded significant amendments to paragraphs on issues and measures in line with normative/legal approaches during the drafting of a final document for the 2015 RevCon.

There is no doubt that efforts for reinforcing norms and legal frameworks regarding nuclear disarmament are crucial. However, pursuing them prematurely without taking into consideration the dimensions of power struggle in international politics may preclude any meaningful accomplishments. Instead, the most urgent task in these difficult times is to pursue realistic and practical arms control tailored to the security environment in key (sub-) regions by launching close dialogues with the countries concerned on developing shared perceptions of the functions and risks of nuclear weapons in geostrategic competition; contemplating the roles of nuclear arms control in managing crises, mitigating tensions, improving relationships among the countries concerned, and maintaining order in the key (sub-) regions; and establishing and implementing regional arms control measures.

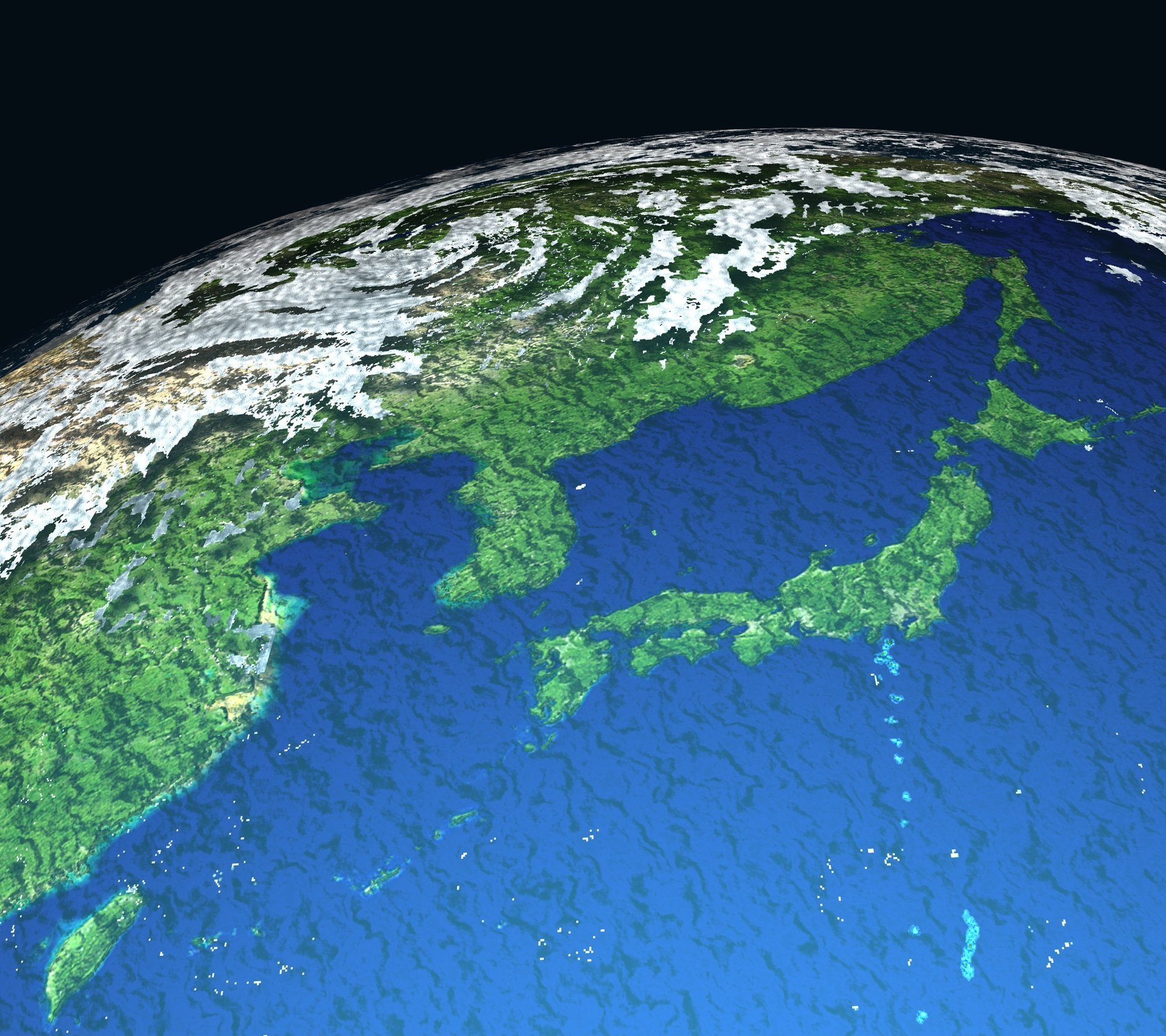

Northeast Asia is one of the regions where such arms control should be explored with the utmost priority. In the past, because of the relatively stable regional security situation under US dominance, few regional arms control efforts had been undertaken by the countries involved in security affairs in Northeast Asia, except the Six-Party Talks on North Korea's nuclear weapons program. However, the regional security landscape has been dramatically changing. A rising China has aggressively pursued modernization of its military, including its nuclear and missile forces, and become more assertive, particularly in the South China and East China seas. Russia's annexation of Crimea, which clearly constitutes a violation of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, undermined the credibility of the NWSs' commitments on security assurance.

The first steps that should be taken by the countries concerned are to commence dialogues on nuclear weapons, missiles and other strategic issues, and to promote multiple confidence-building measures (CBMs). In addition, they could also implement regionally some practical and realistic measures proposed by the Nonproliferation and Disarmament Initiatives (NPDI: a coalition comprising 12 NNWSs, initiated by Japan and Australia) at the 2015 NPT RevCon, including: transparency of information relating to nuclear weapons (and preferably other weapons that have strategic implications, such as missiles, missile defense, and hypersonic strike capabilities); reductions of -- or at least suspensions of enhancements to -- nuclear and missile forces; revisions to the deployment postures of non-strategic nuclear weapons; reductions in the roles of nuclear forces; and visits to Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the people and leaders of those countries. Implementing regional nuclear arms control measures in this region certainly has significant implications for global arms control since three NWSs are involved in security affairs not just in Northeast Asia but also in other regions deemed key in terms of the current power transition.

Since the RevCon, Japan has been criticized for neither joining the "Humanitarian Pledges" nor concurring on a prompt commencement of efforts for a nuclear weapons convention while relying on extended nuclear deterrence despite having suffered atomic bombings. Needless to say, the experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki make Japan and the Japanese people understand the inhumanity of nuclear weapons better than any other country. At the same time, however, Japan must not underrate how serious a security environment it is facing, nor can it afford to rely solely on normative/legal approaches. For ensuring its peace and security and advancing the aforementioned regional arms control, realistic thinking and approaches are essential for Japan. For the sake of a world without nuclear weapons, Japan cannot bypass this difficult and bumpy path.

Hirofumi Tosaki is a Senior Research Fellow of the Center for the Promotion of Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, The Japan Institute of International Affairs.

The views expressed in this piece are the author's own and should not be attributed to The Association of Japanese Institutes of Strategic Studies.